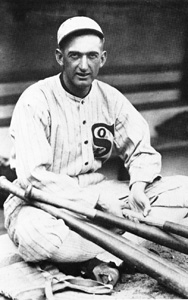

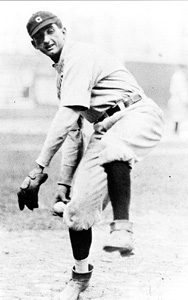

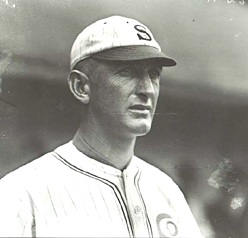

The controversy surrounding the 1919 World Series is most confusing in regards to Shoeless Joe Jackson. The facts (the conspirators' recollections and Jackson's World Series statistics) indicate that Jackson had no involvement with the fix other than being aware that it was going on.

Joe Jackson grew up in Greenville, South Carolina, a town where the men, women, and children worked in cotton mills. Mill life was rough and turnover in the work force was a constant problem for mill owners. The owners discovered that forming baseball teams helped hold their workers. Baseball helped stimulate a sense of community spirit. People of all ages showed up to cheer their favorite mill team and soon the Textile League was established.

In 1902, at the age of thirteen, Jackson went to work sweeping floors in the same cotton mill where his father and brother worked. Before long the managers of the Brandon Mill team asked him to play ball. By the time he was sixteen, Jackson was the best-known player in the Textile League and a local hero. He was a natural ball player. He hit home runs, caught seemingly impossible high flies, and could throw the ball more than four hundred feet on the fly. The fans came to watch Jackson play and he never let them down.

One Jackson fan was local batmaker Charlie Ferguson. When Jackson was fifteen, Charlie took a four-by-four timber of hickory and carved a thirty-six-inch, forty-eight-ounce bat. Charlie shaped that bat to fit Jackson's large and growing hands. When it was finished, the bat was pure white. Charlie knew Jackson liked black bats, so he coated it with several layers of tobacco juice. Jackson affectionately named his bat "Black Betsy." The grandstand crowds would yell down to Jackson: "Give 'em Black Betsy, Joey! Give 'em Black Betsy!"

Joe Jackson began his professional career in baseball with the Carolina Association's Greenville Spinners in 1908. That same year, he married his long-time sweetheart Katie Wynn. In his first season as a professional ball player, Jackson batted .350, hit home runs, and made plays in the outfield that brought cheering fans to their feet. Anyone who saw the nineteen-year-old Jackson play knew he was the best player in the league. While playing for the Spinners, Jackson acquired his nickname. Over the years, many stories circulated as to why he was tagged "Shoeless" Joe. According to Jackson, it happened after he played ball wearing a new pair of shoes. They blistered his feet. The next day when the team was short on players, the manager told Jackson to play despite the blisters. Jackson tried his old shoes, but when those hurt, he played in his socks. In the seventh inning, Jackson hit a triple. The bleachers were close to the field, and as he ran for third base, a fan noticed his socks and yelled, "You shoeless sonofagun you!" Shoeless never played in socks again, but the name stuck.

After one season with the Spinners, the Philadelphia Athletics bought his contract for $325. He played there one season and was traded to Cleveland. He was a star in both Philadelphia and Cleveland, and fans in those cities were sad to see him leave. Jackson arrived in Chicago to play with the White Sox in 1915.

In 1919, known for his natural abilities on the field and his extraordinary home runs, Jackson was well on his way to becoming a baseball legend. Today, however, he is remembered for his association with the Black Sox. Jackson's fate was sealed one night on the final road trip of the 1919 season. Jackson was taking a walk when Chick Gandil approached. Gandil explained to Jackson that seven players had gotten together to throw the World Series, and Jackson would receive $10,000 to help them out. Jackson refused that night and again a few nights later in Chicago. Gandil had raised the ante to $20,000 and remarked that it would happen with or without Jackson. To insure the fix, Gandil used Jackson's name with the gamblers, and Jackson became forever linked to a scheme he tried to avoid.

On the morning of the series opener, Jackson bumped into gambler "Sleepy Bill" Burns in a hotel lobby. Burns, assuming Jackson was a co-conspirator, began talking about some of the details of the fix. This confirmed to Jackson that the fix was in and that his name was being used as one of the fixers. Afraid that he could be implicated in the conspiracy, Jackson went to Comiskey and asked to be benched for the Series. No one knows how much Jackson told Comiskey, but his request was denied.

Jackson played in the World Series and always pointed to his record as proof that he played to win. The real conspirators made intentional errors to lose the games. Their records show a combination of poor hitting, numerous fielding errors, and second-rate pitching. Jackson's performance, in contrast, was blemish-free. He had more hits than any player on either team. He scored five runs and drove in six. His batting average was .375 and his twelve hits set a World Series record. In the field, thirty balls came to Jackson and he made no errors.

The night after the final game of the World Series, pitcher Lefty Williams came into Jackson's hotel room with an envelope. Williams confirmed that Jackson's name was used for the fix, so the $5,000 in the envelope was his. Jackson didn't want the money, but Williams tossed it on the floor and left the room. The next morning, Jackson took the money and went to see Comiskey. He could not get past Comiskey's secretary Harry Grabiner. Grabiner said it was understood why Jackson was there, but he should take the $5,000 and go home. Grabiner said that if anything else was to be done, he or Comiskey would write to Jackson. From his home in Savannah, Georgia, Jackson wrote to Comiskey about the money, but Comiskey never acknowledged the problem. As it turned out, Comiskey was too busy trying to cover up his own knowledge of the fix to be bothered with Jackson.

The grand jury hearings got under way in 1920. Jackson, who never learned to read or write, was manipulated by Comiskey and Comiskey's lawyer Alfred Austrian. If the truth were discovered (Jackson had spoken with Comiskey about the fix and the $5,000 long before an investigation into the World Series began), Comiskey would have to admit he know about a fix, but publicly denied it and re-signed players he knew were corrupt. Jackson's story would tarnish Comiskey's reputation, and Comiskey risked being banned from baseball. Jackson, operating on the belief that Austrian was also his lawyer, followed Austrian's instructions during the grand jury hearings and ended up being indicted.

By the time the trial for the accused White Sox began in June 1921, it was discovered that much of the case file was missing, including records of the grand jury testimony of the players. The trial lasted several weeks, but the jury deliberated for only a few hours before they found all defendants not guilty of all charges. The newly appointed commissioner, Judge Landis, did not treat the players as lightly. He banned all the Black Sox from professional baseball. Jackson was banned for not telling his team about the plan to fix the Series.

Shoeless Joe was thirty-three when his professional baseball career abruptly ended. He and his wife Katie moved back to the South, where he worked for a while in their dry-cleaning business (years later he operated a liquor store). Through the years, Jackson played ball whenever he had the chance. He accepted many offers to play semi-pro and exhibition games. The fans still loved watching Jackson play. Jackson loved the game and played for a long as his health allowed. He finally stopped playing baseball in 1933, at the age of forty-five. Even after his death, people still made attempts to have Jackson reinstated. Only when he is reinstated will he be eligible for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. There are those who believe the Hall of Fame will never be complete without him.

According to Joe Jackson, the most famous line to emerge from the Black Sox Scandal was never actually spoken. A newspaper reported that as Jackson was walking through a parking lot after the grand jury hearings, a small boy walked toward Joe and said, "Say it ain't so, Joe." Joe was quoted as replying "It's so kid, it's so." Jackson said he left the courtroom, a deputy sheriff asked for a ride, the two got into the car together and left. No one else spoke to him.

Above text taken from here